Timeline of Revolution

1789-1799

Jacques Louis David never finished his sketch of the Tennis Court Oath. In a sign of how quickly politics changed, many of the figures celebrated in the work were denounced as traitors before he could begin painting.

Disgusted by the submission to the revolution by his brother the king, the Count of Artois fled abroad to raise a foreign army to invade his homeland.

Working women marched to the king’s palace and forced the royal family to return to Paris as de-facto prisoners. Without this intervention, the revolution could well have turned out very differently.

‘Sans Culottes’ literally means those without the fancy pants worn by nobles. Their workers’ trousers were once a mark of social shame, but soon became required of all good revolutionaries.

1775-1783

American War of Independence

France is the most powerful country in Europe, but has been in decline since the end of the reign of the ‘Sun King,’ Louis XIV, in 1715. It supports the American colonies to weaken its arch-rival, the British. A young Marquis de Lafayette gains fame fighting alongside George Washington, but the cost of war helps push the monarchy toward bankruptcy.

1789

Spring 1789

The Estates General

King Louis XVI desperately needs to raise new taxes, but the nobility refuses unless he convenes a nationwide Estates General to enact reforms – a demand that hasn’t been made for 165 years. This is a humiliation for a supposedly absolute monarch. Everyone expects something very different from the convention: many nobles want a limited constitutional monarchy, some radical thinkers dream of a democratic republic, and the masses just want relief from years of terrible famine.

June 20, 1789

The Tennis Court Oath

The Estates General is doomed from the start. After disagreements over how voting will work, the commoners break away and simply declare themselves the new legislature – the revolution has begun. In response, the regime locks them out of their meeting hall. The delegates reconvene at a nearby tennis court and pledge not to be dispersed without bloodshed.

July 14, 1789

The Fall of the Bastille

Louis surrounds the rebellious capital with soldiers, including foreign mercenaries. Parisians arm themselves and launch a daring and bloody attack on a symbol of monarchical tyranny: the dreaded fortress of the Bastille.

July 17, 1789

Flight of the Emigrés

Stunned by the fall of the Bastille, Louis backs down and removes his troops from Paris. He even dons the tricolor cockade, the symbol of the revolution. Disgusted, his brother the Count of Artois leaves the country, beginning an exodus of nobles. Abroad, they plot to destroy the revolution and encourage European rivals to invade their homeland.

Summer 1789

The Great Fear

The turmoil in the capital leads to a sense of anarchy in the countryside. Peasants riot and pillage noble estates.

August 27, 1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man & Citizen

Inspired by the American Bill of Rights, the new government proclaims Lafayette’s Declaration of the Rights of Man & Citizen. Lafayette also places himself at the head of the new National Guard, which replaces the king’s troops in Paris.

October 4, 1789

The Women’s March on Versailles

In the midst of deadly famine, an armed mob of women marches out to the king’s palace in Versailles. They force the royal family, under threat of violence, to return with them to Paris, where they can be under the close watch of the revolutionaries.

1790

July 14, 1790

Fête de la Fédération

An uneasy truce reigns. No one is quite sure if the king is still in charge, or if he is a prisoner in his own palace. Nonetheless, the first anniversary of the fall of the Bastille brings together the old regime, the new government, and a huge celebratory crowd. It is the height of Lafayette’s power, and the last time all the factions will be at peace.

1791

June 20, 1791

The Flight to Varennes

After nearly a year of virtual captivity, Queen Marie Antoinette orchestrates an escape attempt to her Austrian homeland. They are captured near the border and returned to Paris under guard. Despite it all, the king remains on the throne, even though there is no longer any doubt that he is a prisoner of the revolution.

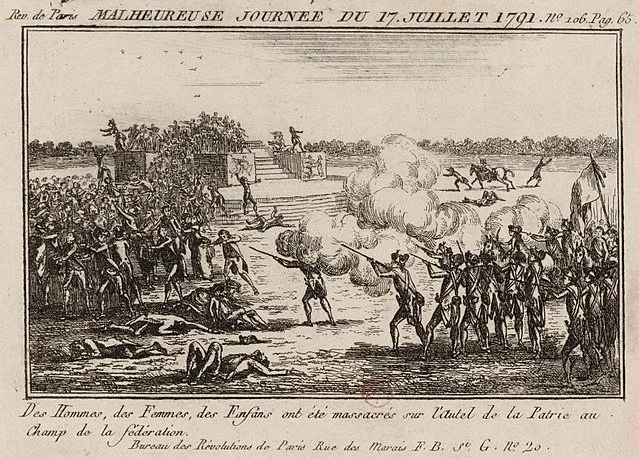

July 17, 1791

Massacre of the Champs de Mars

July 1791 is very different from the peaceful Fête de la Fédération the year before. A large crowd rallies at the Champs de Mars to demand the official removal of the king. Fearing a threat to his own growing power, Lafayette orders his troops to fire on the mob. His reputation will never recover.

September 3, 1791

Constitution of 1791

Under duress, the king ratifies the first constitution in French history. It limits his authority and guarantees many rights, but it prevents the lower classes from voting – ensuring that the furious working class, known as the ‘Sans Culottes,’ will never accept it.

1792

1792-1815

War

Other European monarchies, fearing revolution in their own countries, invade France to restore King Louis to his full power. France will not be at peace until the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo in 1815.

August 10, 1792

‘The Second Revolution’

It is time for the Sans Culottes to have their say. In a violent uprising led by Georges Danton, working class Parisians kidnap the royal family and force the election of a new republican government. A dismayed Lafayette attempts to march his army on Paris to put down the rebellion; his troops refuse the order and Lafayette flees to Austria, where he is imprisoned. His role in the revolution is over.

September 2-7, 1792

The September Massacres

All of the fighting men of Paris are needed at the frontlines. Afraid that royalist prisoners will escape and murder their families, they launch a series of extralegal tribunals that execute more than a thousand prisoners.

1793

January 21, 1793

The Execution the King

After a lengthy trial, King Louis XVI is condemned for treason and executed by guillotine. Among those voting for death are the Duke of Orleans, a prince of the blood and cousin to Louis.

1793-1796

Civil War

Angered by conscription and efforts to limit the power of the Catholic church, the western Vendée region goes into revolt, starting a bloody civil war that will rage for years. Atrocities on both sides make this conflict the darkest chapter of the revolution.

May 1793

The Committee of Public Safety

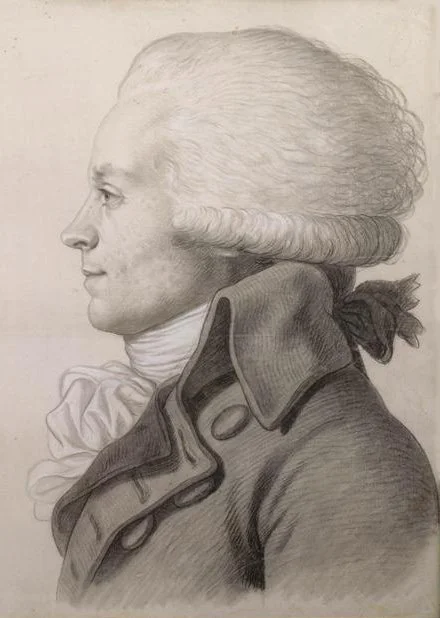

The republican radicals who are now in power, known as the Jacobins, are fighting their own political civil war. The left wing members, known as the “Mountain” (so-called because they sit high in the bleachers), led by Maximilian Robespierre, turn on their former allies, the more moderate “Girondins,” led by Jacques Pierre Brissot. Eventually, nearly all leading Girondins are executed or commit suicide. Robespierre takes control of the Committee of Public Safety, a twelve-member executive council with nearly unlimited power.

Summer 1793 - Summer 1794

The Reign of Terror

The Committee of Public Safety faces an impossible situation: Spain and Austria have invaded the frontiers, a civil war has set the Vendée aflame, new revolts erupt in major cities angered by the execution of the Girondins, and unrest in the streets of Paris threatens the very existence of the government. In a desperate attempt to save the revolution, the Committee of Public Safety passes laws allowing for the swift trial and execution of anyone suspected of treason. Thousands are marched to the guillotine.

October 16, 1793

Execution of the the queen

Queen Marie Antoinette is finally guillotined after a long and humiliating trial.

1794

Spring 1794

The Revolution Devours Its Children

An increasingly paranoid Robespierre strikes out against his rivals and former allies. First to fall is the ultra-radical Jacques Hébert, who had been agitating for free grain and proto-socialist reforms. More shockingly, Robespierre denounces and executes the ‘giant of the revolution’ himself, George Danton.

July 27, 1794

The Fall of Robespierre

Opponents of Maximlian Robespierre, afraid of further purges, rise up and denounce him in the convention. After a standoff between rival armed forces, and a botched suicide attempt, Robespierre is taken into custody. He and more than one hundred of his supporters are sent to the guillotine.

1795

1795-1799

The Directory

A five-member council takes over ruling the country, led by Paul Barras. They are more concerned with preserving their own power than pursuing any kind of ideological vision. Venal and corrupt, they repress the right and left with equal cynicism. They will, however, manage to stay in power until the rise of Bonaparte.

20 May, 1795

Revolt of 1 Prairial Year III

The last gasp of the Sans Culottes. The streets erupt in one last cry for bread and social justice. Mobs from the working class eastern sections manage to seize the Tuileries Palace, but are overwhelmed by the army and royalist gangs.

1796

May 1796

The Conspiracy of Equals

In a preview of the vanguard Communism that will emerge in the early 20th century, François-Noël Babeuf, who styles himself ‘Gracchus’ after an ancient Roman revolutionary, leads a small, doomed uprising in favor of radical equality.

1799

November 9, 1799

End of the Revolution

The rise of General Napoleon Bonaparte and his violent seizure of power as ‘First Consul’ brings to a close a decade of revolution. Napoleon’s wars will claim tens of millions of lives, and it all ends where it began. The executed king’s brother was restored to the throne after France’s defeat in 1815.

This cartoon depicts Robespierre executing the executioner, having run out of anyone else to guillotine. The Reign of Terror was partly so shocking because it targeted revolutionary heroes nearly as much as aristocratic reactionaries.

The Bastille was raided not to free prisoners, of whom there were only seven, but to secure the cache of gunpowder kept inside.

The caption reads "Men, Women, Children were massacred on the altar of the fatherland at the Champ de la Fédération."

Though not a tradesman himself, Georges Danton was the forceful leader of the working class. His execution at the hands of Robespierre was one of the most shocking moments of The Terror.

Robespierre was a curious figure: powerfully charismatic from the podium, he was largely isolated in his private life. He began as a staunch opponent of capital punishment before embracing the guillotine as a means to deal with those who fell short of his rigid standards of revolutionary ‘virtue.’

This drawing by Jacques Louis David shows the queen being trundled to the guillotine dressed as a commoner. The downfall of the royal family provoked invasion by her native Austria.

Once a Jacobin himself, General Bonaparte used his troops to disperse the government. Soon crowning himself Emperor Napoleon I, he brought the revolution full circle.

The Reign of Terror in Context

The historical consensus for the death toll of the so-called Reign of Terror stands at about 16,000. The vast majority of these killings occur as reprisals during uprisings in the Vendée and Lyon, and should probably be accounted as casualties of civil war rather than ‘the Terror.’ The number of political executions is somewhere around 2,000: the death toll of a Napoleonic skirmish, or a pale fraction of the poor who died from starvation and neglect every year during the old regime.

Do not let the drama of the Terror obscure the staggering achievements of the revolution. The merits of the revolution will be debated forever, but one thing is certain: the French Revolution was one of the very few moments in all of human history where the powerless managed to seize control from the powerful.

The American Revolution decided which elite should rule the colonies, the king or the local de-facto aristocracy. George Washington was, after all, one of the most powerful men in the new world. Unlike the American one, the French Revolution went far beyond the elites to improve the lives of common people. It granted unprecedented rights to women, including suffrage and the right to divorce, and freed enslaved human beings throughout the empire. It sparked a scientific revolution by introducing the metric system and replacing Catholic schooling with public education of the highest standard. It attempted to rewrite time itself by creating a new calendar that celebrated nature and the common people in place of gods and kings. It proved beyond doubt that the humblest person is as capable, and as worthy, as the highest. Even divine monarchs are mere mortals before the guillotine. Even the lowest peasants are potential heroes of the republic.

In some way, all subsequent revolutions harken back to the fall of the Bastille. A revolution of the human spirit began in Paris in 1789. It has never really ended.

“There were two ‘Reigns of Terror,’ if we would but remember it and consider it; the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the ‘horrors’ of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heartbreak? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror — that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves.”

—Mark Twain