DESIGNER DIARY

Revolution: PAris

Theme & Mechanics in Revolution: Paris

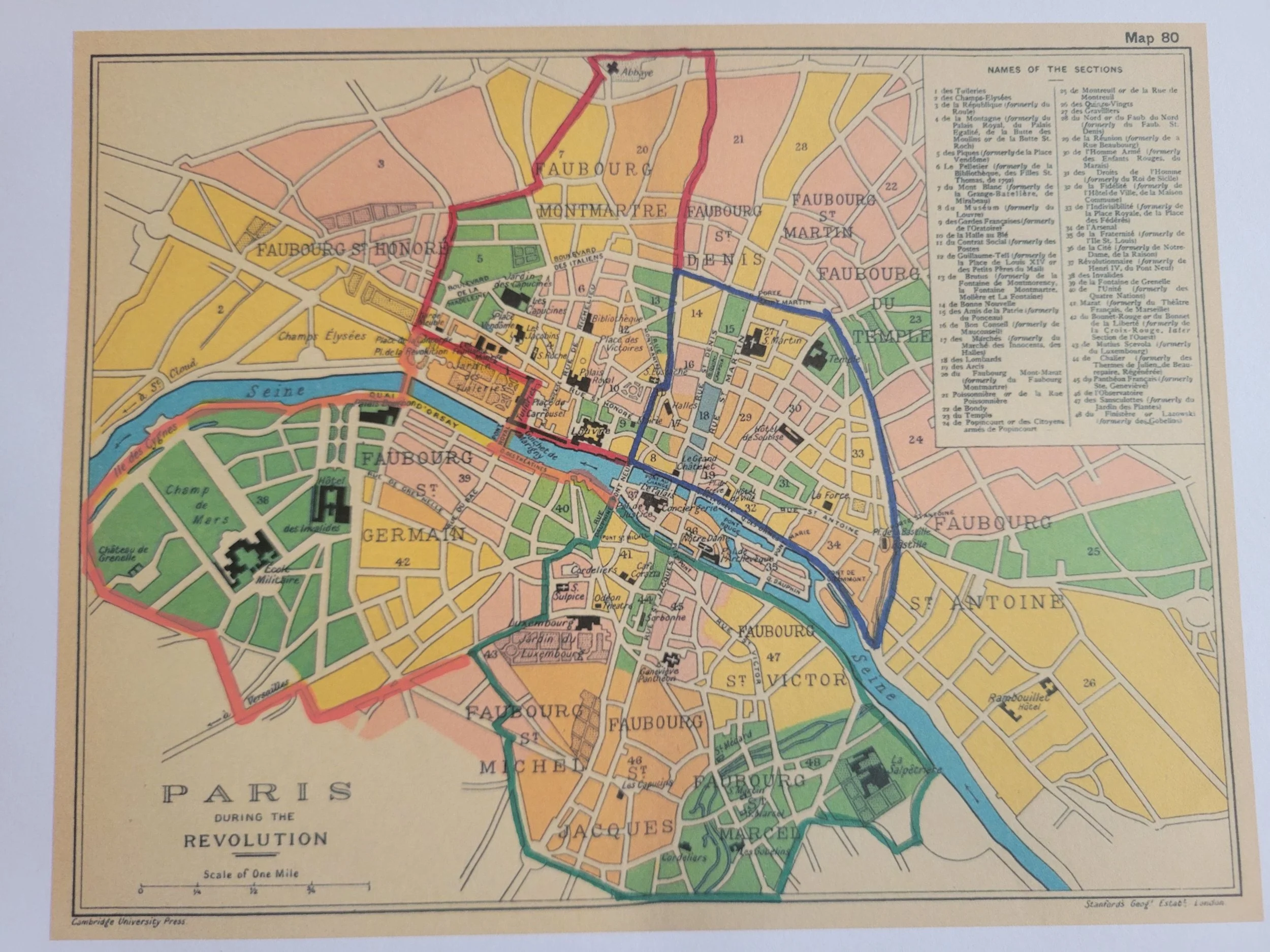

REVOLUTION: PARIS BEGAN AS PURE THEME. I had been taking a deep dive into the French Revolution and thought, hey, a Paris street map, some barricades popping up here and there, a little guillotine — this could be a fun board game, right?

I wasn’t even in the tabletop hobby at the time. I’d grown up with Risk, Axis & Allies, Hero Quest, and plenty of Magic: The Gathering, but like many, my familiarity with modern games topped out at Catan and Pandemic. So I decided on a crash course — I watched the entire catalogue of Shut Up & Sit Down and played every digital adaptation I could find, with special appreciation for games like Istanbul, Age of Wonders, and Everdell. It was a stroke of luck that I downloaded as a first rulebook to study that of Pax Pamir, by a designer who soon became my favorite, Cole Wehrle. My journey into gaming became over-the-board with the opening of the delightful Mystery Box Games, in my hometown of Easton, Pennsylvania.

I was intrigued by what tabletop games had become, drawn in by the concept of games as art objects. I loved seeing designers’ names bannered on the box, like authors or directors. I was overawed by the systems and complexity of games like Gloomhaven and Twilight Imperium. I was starting to get a handle on what I wanted my game to be — strategic, medium-weight, and deeply thematic, of course.

But I had no idea what it would look like. I mean, I had a sense of what it would look like — a map, naturally, and character cards featuring the many colorful personages of French revolutionary history. But what, exactly? Who, exactly?

It’ll be fun, they said ….

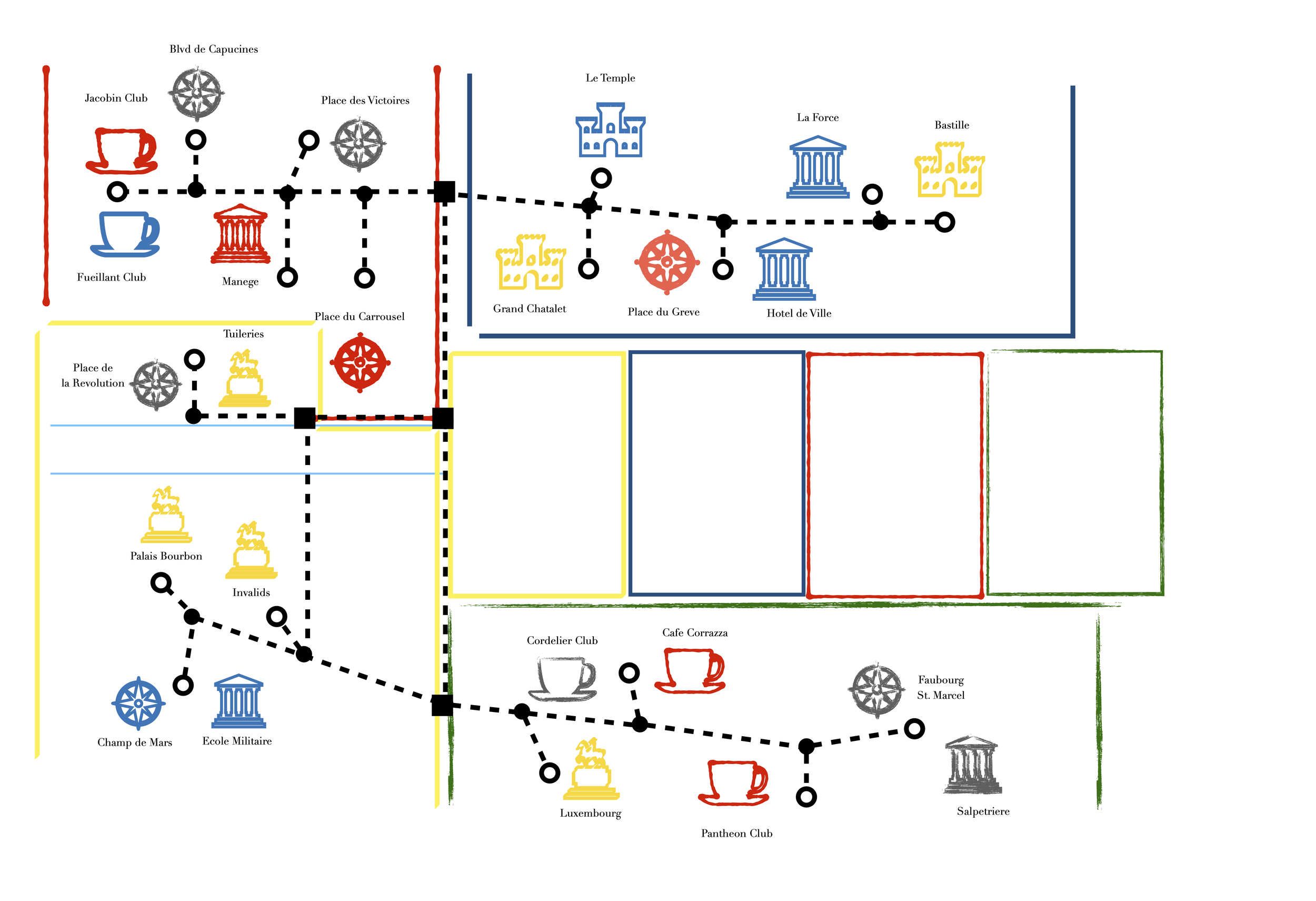

We tried, unsuccessfully, to incorporate streets into a game originally conceived to be about “the streets of Paris.” Barricades remain in the game, but play a much smaller role than originally imagined. It’s just as well — barricades were an ancillary feature of the 1789 revolution as compared with the 1832 revolution made famous by Les Misérables.

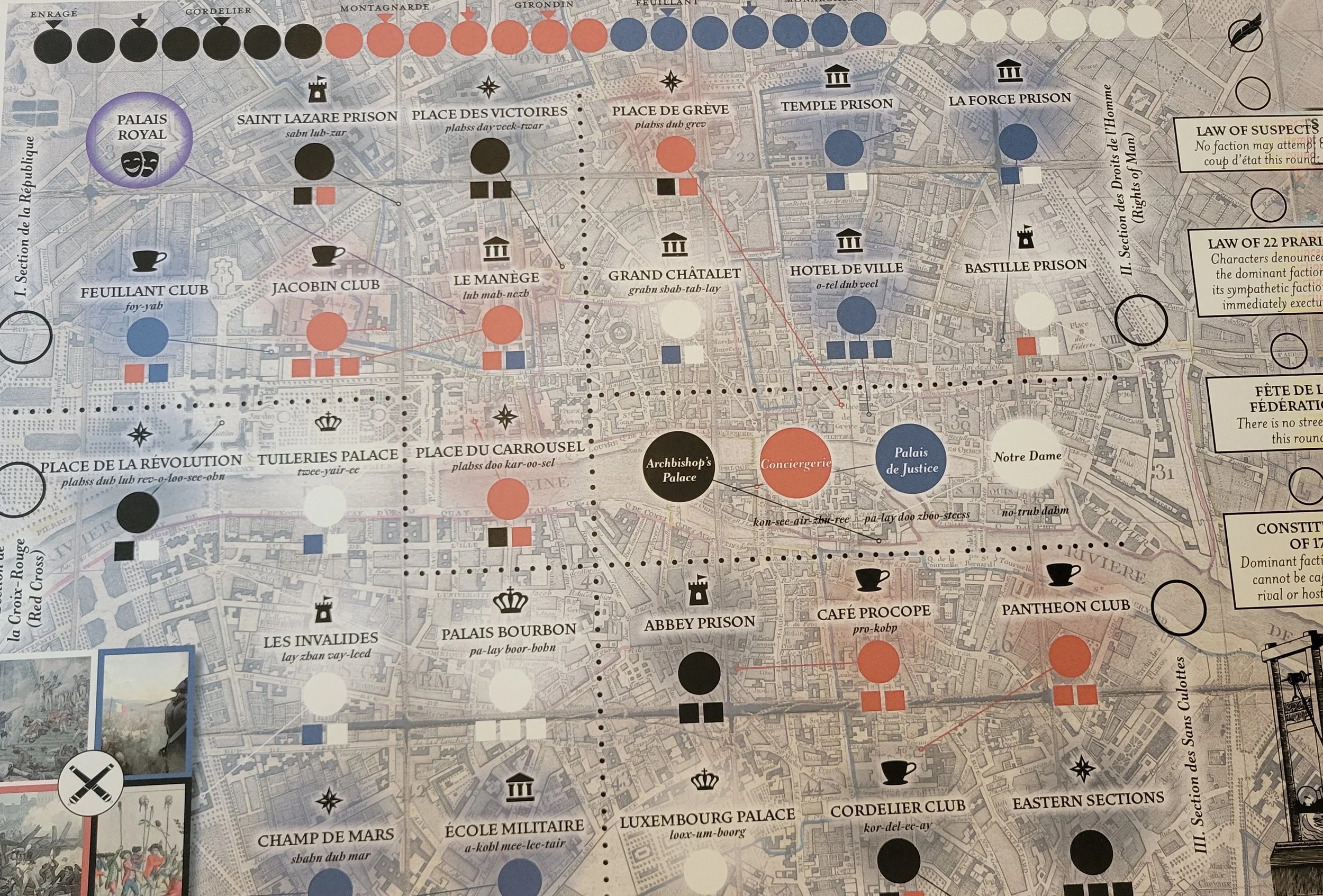

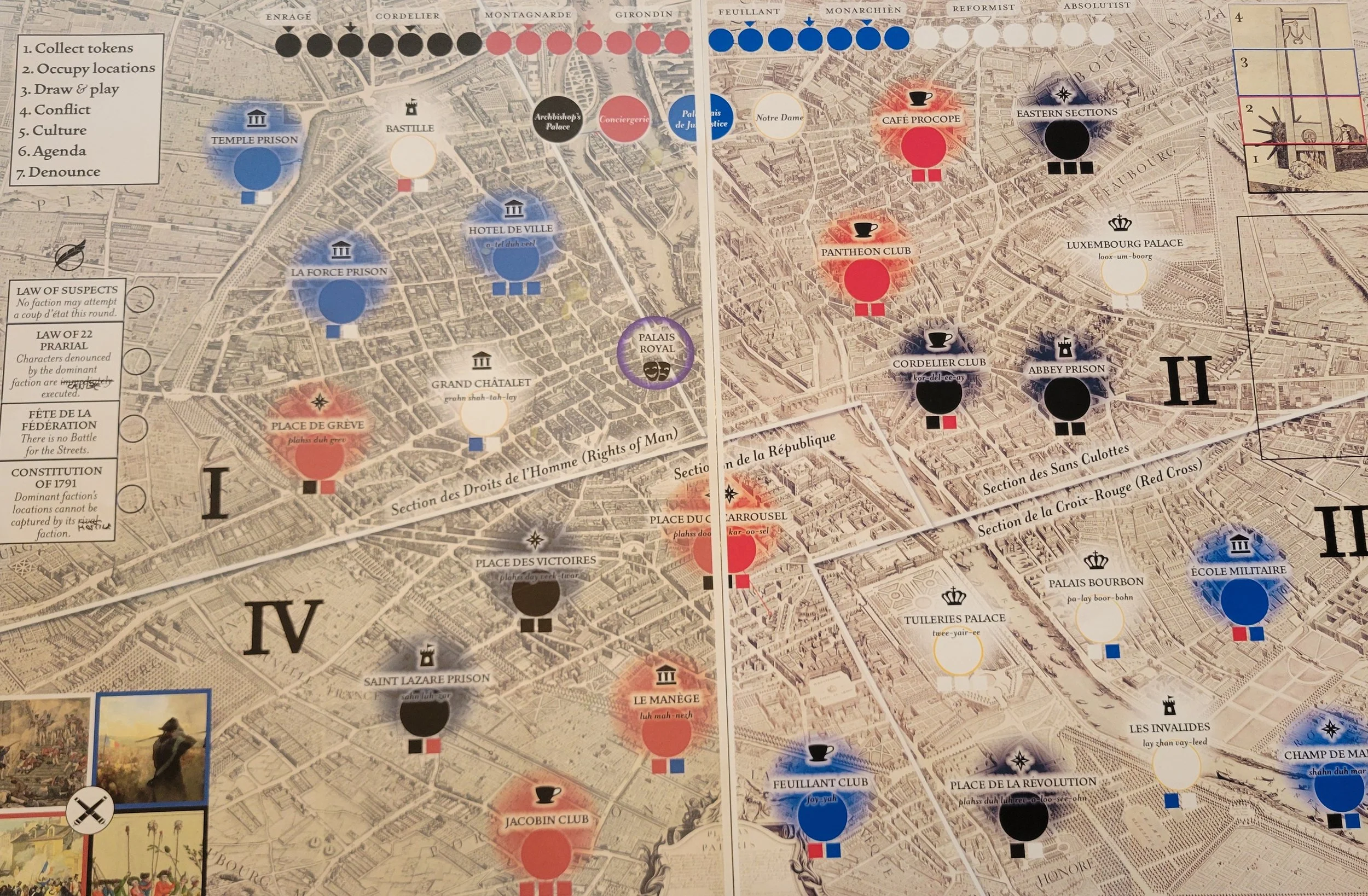

Rather than imposing the idea that quarters of the city correspond to each of the four factions, the mechanic arose organically from plotting out the landmarks of the revolution.

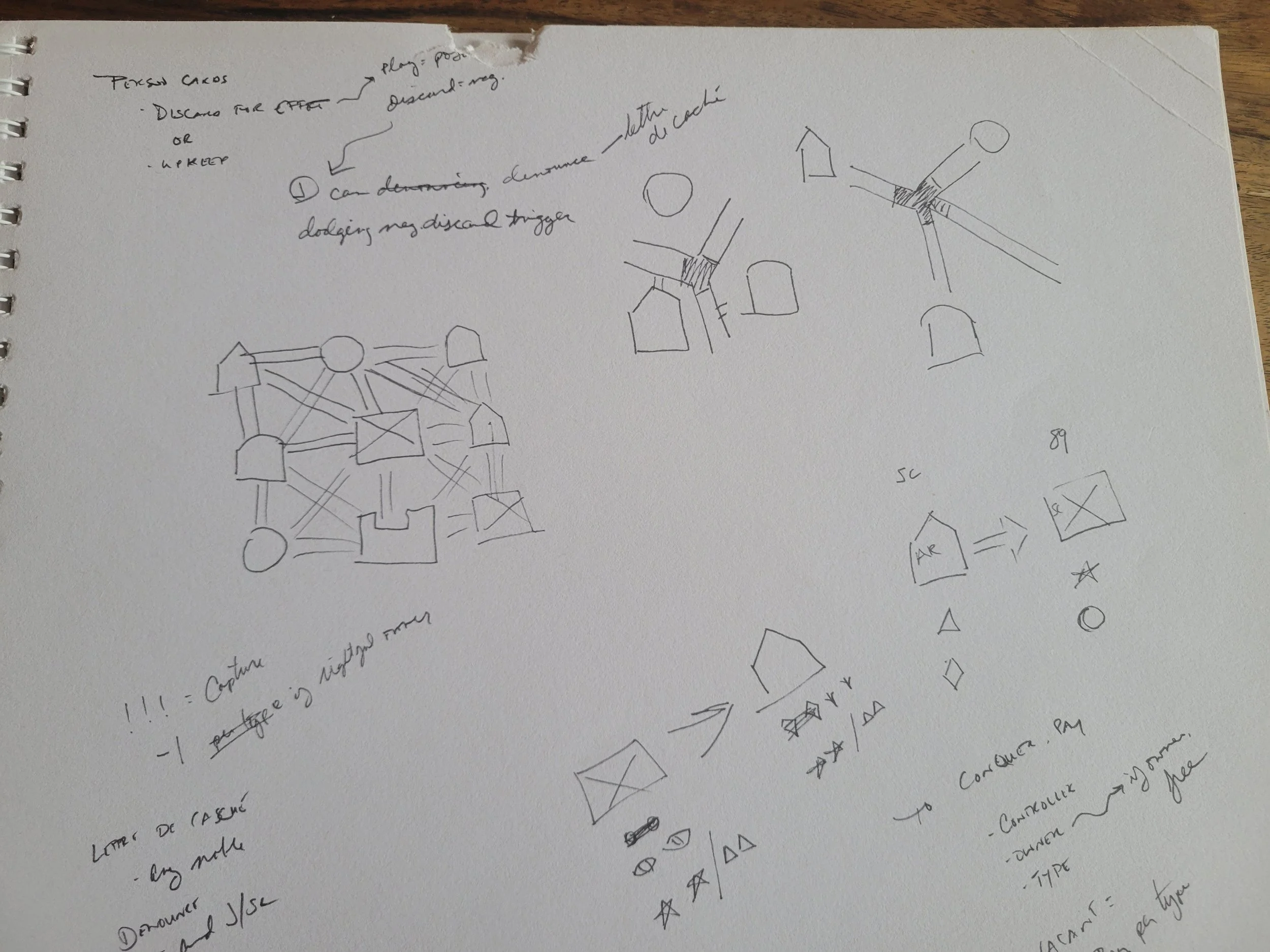

The first conception of the game’s asymmetric resource system written, literally, on the back of an envelope.

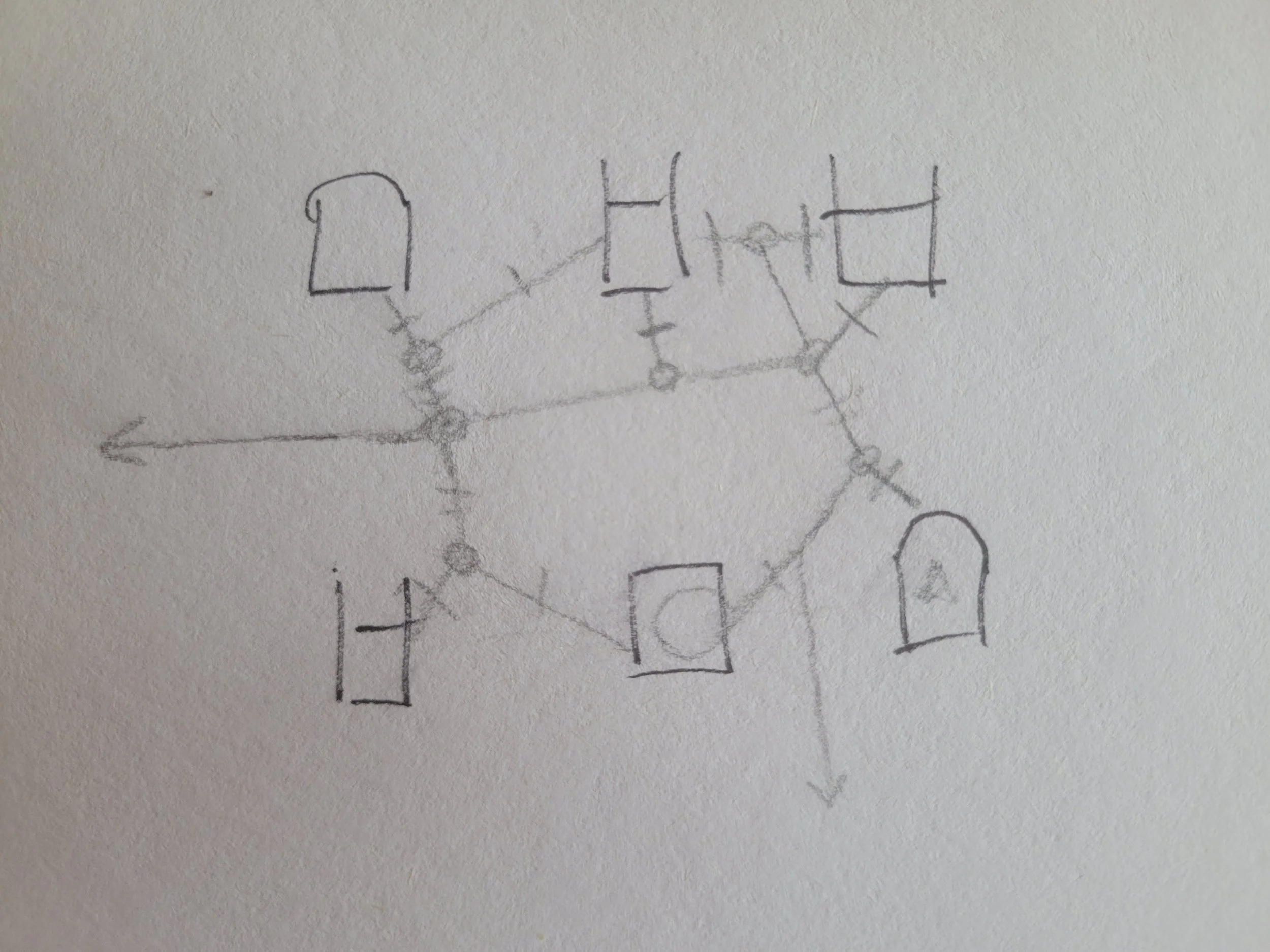

The original victory condition was based on area control, but we realized that the revolution was not about controlling the physical city, but influencing and governing its people. To that end, we created the ministry (whose four “locations” we were able to situate nicely in the Île de la Cité, according to their historical context).

IN THE GREAT PUSH-PULL of theme and mechanics, it’s remarkable to me how many mechanics came directly from the theme. We often think of games (and I think it’s true of many games) as themes wrapped around pre-existing systems. Revolution: Paris has been the opposite. I looked at the history and tried to determine how it all worked — what was the “game” that drove the course of real events?

I started by making a huge list of historical figures, ending up with well over a hundred. What I noticed (aside from the fact that nearly half died violently during the bloody tumult) was that they broke down remarkably evenly between the four factions I had somewhat arbitrarily created — the monarchy, the constitutionalist nobles, the firebrand republicans, and the populist masses. The fact that history reinforced this division helped assure me that I was on the right track.

The game really began to open up when I realized what the resources had to be (in terms of the game and of history itself): the elements of political power. I came up with authority, prestige, zeal, and populism. These ingredients matched up beautifully with the factions I was forming — both in what they possessed and what they needed. For instance, the king had all the trappings of despotic power, but he and his court lacked the political vigor to survive when arbitrary authority was no longer respected. Likewise, the republican Jacobins had plenty of passion, but no legal authority to enact their ideas.

This conception of political resources helped define not just the individual factions, but the relationship between the factions. This interdependence was the origin of the asymmetric exchange rate, perhaps the core mechanic. The constitutionalists of the Society of 1789 have prestige in spades, what with their money and titles and high ideals, but they severely lack the populist support enjoyed by the street orators and organizers. What is cheap to you is precious to your opponents, and vice versa, so you’ll have to negotiate carefully in order to win.

Speaking of … how in the heck do you win? Revolution: Paris had been in development for over a year before I had any idea of how to win the darn thing. So, back to the well. What did winning mean, historically? Over the course of the revolutionary decade, governments, often internally divided, rose and fell rapidly. “Winning” the revolution meant creating a stable, unified government. Therefore, that would be the objective of the game. There would be four governmental positions, corresponding to each of the factions; control them all and win.

The evolution of Robespierre.

Characters at various points had numerous effects and abilities. These were eliminated in the name of strategic clarity.

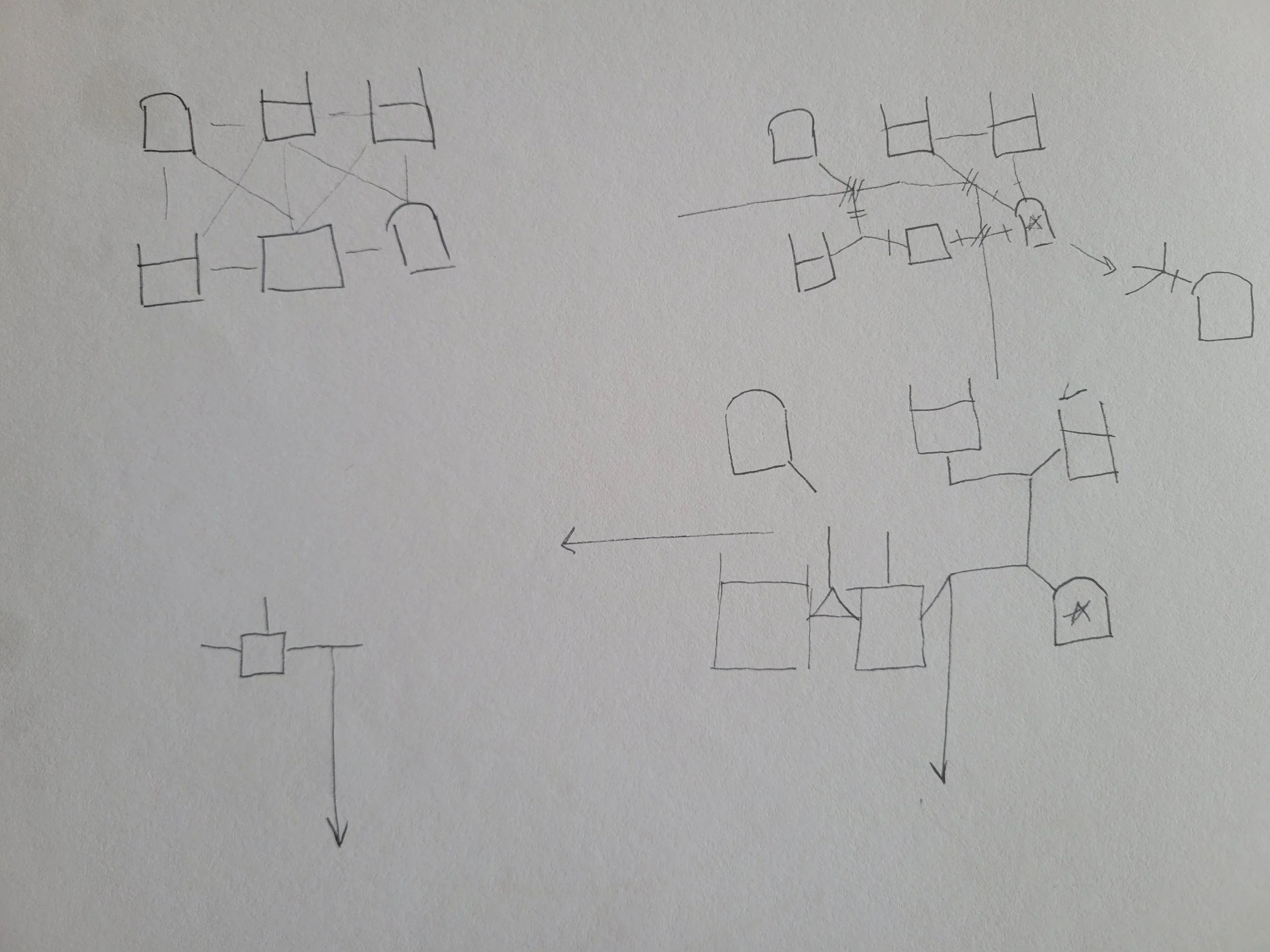

THOUGH THE GAME HAS ENDED UP FAIRLY COMPLEX, the process of development has largely been one of shrinking, shedding, and simplifying. (For instance, there was an entire dudes-on-a-map aspect of units and combat that clung on for years before finally getting the guillotine). The mantra has always been to keep the mechanics as simple as possible while incorporating as much theme as necessary to bring the story to life.

I knew from the beginning that we had to include culture in some form — the “hearts and minds” battles of arts and letters and even fashion raged right alongside those of politics and armed conflict. But what, in real life, does culture do? In the political context, it serves as a propaganda tool to sway the people. Therefore, in the game, there had to be something to sway. Thus was born the political spectrum. You’ve got to leverage culture to align the political spectrum with your faction as part of the win condition.

Our big stack of character cards was always daunting, but I knew I wanted to incorporate as many as we could reasonably manage. The remarkable dramatis personae is what has always kept me returning to the French revolution — from the famously virtuous but sanguinary Robespierre to the obscure but fascinating spy and trans pioneer the Chevalière D’Eon. I took as a starting point the crucial Marquis de Lafayette. To figure out what he does in the game I looked back to what he did in the revolution. I finally realized what he did, or tried to do, was reach out and unify the disparate factions (under his own leadership, of course). This gave rise to the idea of “co-option,” whereby under certain circumstances you can count another player’s characters as your own. This mechanic soon evolved beyond Lafayette to become a central concept in the game.

We were getting there. But in the words of Robespierre, “Do you want a revolution without a revolution?” What’s a revolution without the lightning coup d’etat? So we came up with the mechanic of playing some cards face down as part of a hidden conspiracy, with the ability to reveal them all at once for a powerful turn. This had the added benefit of providing a comeback mechanism for those fallen behind, as well as the ability to overcome stalemate when other players work together to keep the leader in check. Once again, it was theme that came to the aid of mechanics.

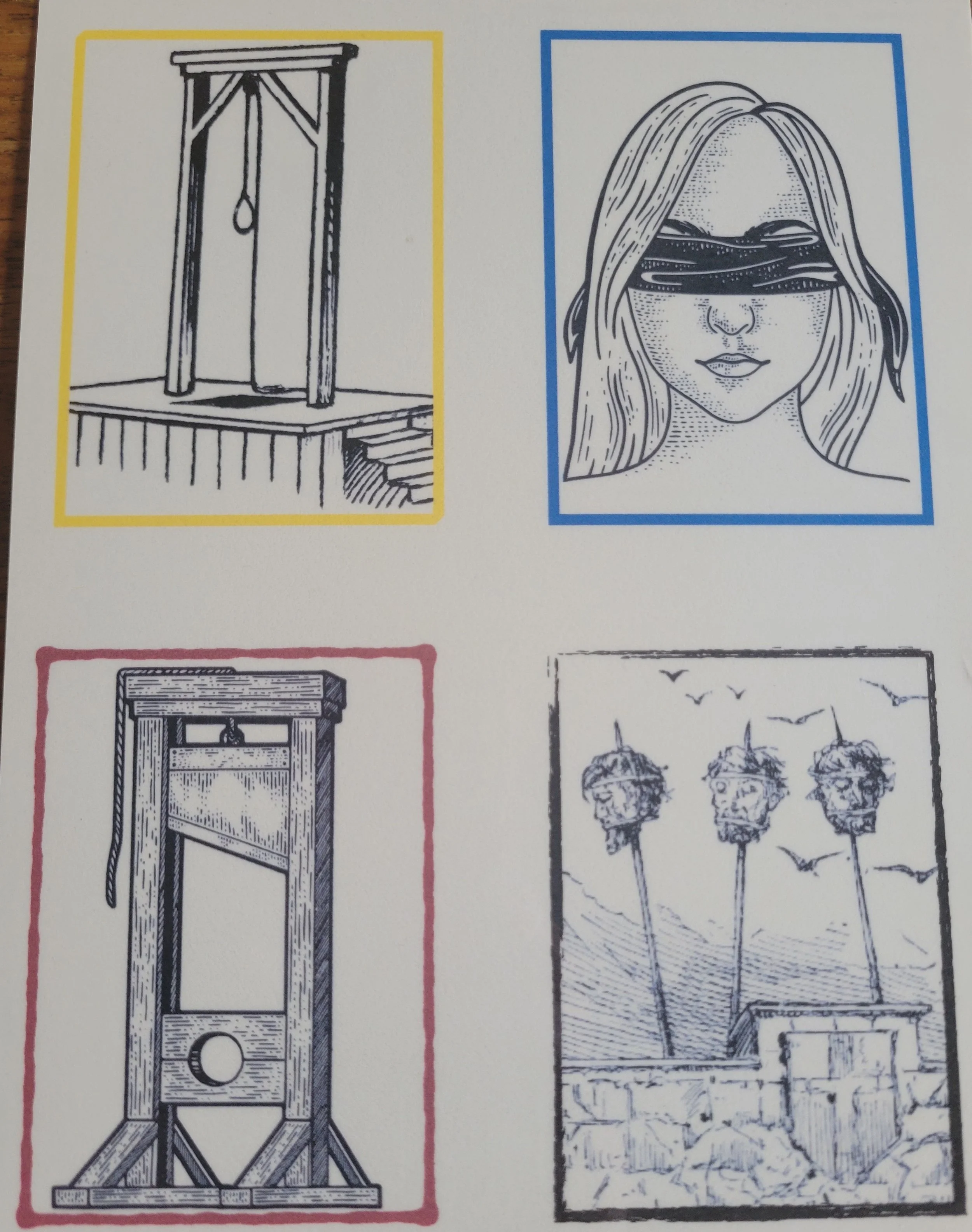

For the sake of accuracy, each faction once had their preferred method of execution, but this seemed too fiddly. It’s the French revolution, it’s the guillotine for everyone!

One last thing, but it’s a big one. A big, sharp one. We can’t have the French revolution without Madame la Guillotine. Its blade loomed over the design process as we severed idea after idea. In the end, it tied up nicely, we think, with another loose end. I knew we wanted the sliding political spectrum to have some impact on the game rules, and we realized that as it shifted left and deeper into anarchy the guillotine would become more active. We came up with the idea of being able to denounce characters — and the further left the spectrum, the fewer denunciations required to “shave them with the national razor.”

The Event and Decree decks were ultimately scrapped for being too cumbersome, though decrees live on in a much simplified form as a limited set of agendas that the leading faction can enact.

For years, the game featured a full-scale warfare system, complete with faction-specific units and dice-driven combat. However, it was always time-consuming and problematic. Once again, the theme proved clarifying. While armed combat did occur in Paris, the 1789 revolution was a psychological struggle, not an area-control military affair. A combat system was mechanically unwieldy and thematically unnecessary. Armed conflict lives on the in the form of the Battle for the Streets, but it serves an appropriately auxiliary function.

It just wouldn’t be the French revolution without a guillotine.

I KNEW, ULTIMATELY, THAT WE WANTED A COMPELLING STRATEGY GAME, not a historical simulation. In ways great and small, elements of historical accuracy were sacrificed in the name of streamlined, strategic function. After all, we want the game to inspire interest in history, not necessarily to teach history. Still, the mechanics of this game would not exist if they were not informed, time after time, by the theme they mean to evoke. Politics is often referred to as a game. We hope we’ve captured that for you here with Revolution: Paris.

More maps! And these are just for the prototype. The final version will feature all original artwork.